What’s The NMH Farm Without Its Animals? A More Sustainable One.

By Jessica Zhang

If you’ve noticed that the barns have been quiet recently, you’re not the only one.

Last year, I visited the farm almost every week. I’d stand against the metal fence and peer at the draft horses, Belle and Shorty, who’d always stare back through their tufts of blonde fur. If the barn was open, I’d say hello to the goats. This year, however, all of that has changed. Over the summer, the goats were sold. The farm then lost its two beloved horses– one to a stroke, and one to retirement. When I opened my email on a warm day in July, I found that Jake Morrow, the former farm director, wrote in a heartbreaking eulogy that “[Belle and Shorty] gave countless students the opportunity to learn the deep joy of being around horses.”

When I visited the farm at the beginning of the semester again, I was deeply disappointed by the absence of familiar friends. Most of all, I hated to be the bearer of bad news: all the livestock are gone, and they aren’t coming back– at least not for the foreseeable future. The NMH farm is undergoing its most drastic overhaul in a decade, and this time, it will not be accompanied by farm animals. It was a decision by the administration that left many with more questions than answers. After all, why would NMH give up something so integral to the farm? Had it not been a staple of its program, its culture, and its traditions for well over a century?

Talia Baron 26’, who tended to the animals for her farm work job last year, echoed this sentiment. “The whole program was a big part of our community,” she said. They were special, because “Some people are scared of bigger animals, but our animals were so sweet and well-tempered.” During her many hours at the farm, she would clean stalls, feed the horses, and care for the goats. It gave her a deep connection and appreciation for them. “I would like to get our animals back,” she admits.

At first, I was a staunch advocate of this. Like Talia, I too missed the draft horses and the sound of their hooves as they meandered around their pasture. I missed their quiet strength; the ease they’d bring to me when I was homesick. I missed pointing them out to my parents whenever they stopped by campus, as if their presence was not just a point of school pride but also a personal one. After all, how many schools could boast that they owned a pair of beautiful draft horses?

The cost of owning those animals, however, was incredibly steep. Staff had to attend to the animals at all times, including over summers and winters and the weekends when workjob students were away. With few people qualified to man the equipment and care for the livestock, Jake Morrow had been the one shouldering nearly all the labor.

“It was a very demanding job,” said Jake, who recently pivoted away from farmwork to teach English. “It was seven days a week, every morning, every evening. Someone always has to be there. For six years, that someone was me.”

During his six-year tenure, Jake saw a lot of change. The farm went through a rotating cast of livestock that included dairy cows, cattle, draft horses, goats, laying hens, and even oxen– though few animals overlapped. For Jake, his work was endless. Since handling draft horses required a specialized skill set, only he could do it. When COVID-19 hit, and work job students left campus, he was the one cleaning their stalls, keeping them fed, and caring for the farm. Even with all these animals, however, the farm’s primary purpose was still to grow vegetables; the animals were more of a bonus. But they have always been a cornerstone of NMH history.

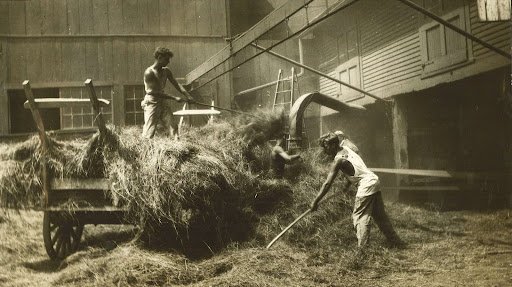

“Every private school in the 19th century needed a farm to sustain life on campus,” said Peter Weis, the school’s archivist. As he regaled old stories of the farm in his dim-lit office, I got the opportunity to look at some photographs taken over the years. Back in the early 1900’s, roughly half of the students worked at the farm. It was critical work; in an isolated school like NMH, far from distribution centers in the cities, it was impossible to get food from external sources. Without refrigeration, milk could hardly last the trip to campus.

At one point, NMH ran a dairy farm with around 200 heads of cattle. And they were pretty darn good at it, too. In the 1920’s, the herd was named a championship herd for the quality of their dairy products, and they became the third best herd in New England. In 1927, the herd was unfortunately infected with tuberculosis, which ended that chapter of NMH dairy herd dominance.

A decade later, NMH was caught in a wave of new technological and societal advancements. Between 1927 and 1960, the U.S. became increasingly urbanized. The mass production of dairy made it cheaper to buy milk than to produce it, which led to the herd being sold in 1961. The farm was shut down shortly after. Peter remembers that scene of abandonment very vividly: “It’s just like people got up and left.”

Luckily, that wasn’t the end. The farm eventually did return in the 1970’s, buoyed by the progressive back-to-the-land movement.

But to understand the farm’s present circumstances, it’s important to learn why it was created in the first place. It was out of necessity that NMH owned hundreds of dairy cows, that they sent the Mount Hermon boys to the woods every winter to log timber. This was the reality of a time before the comforts of technology sheltered us from the hard labor of lugging around hay to keep the cows fed, or cutting down trees to keep the dorms warm.

The modern world has made it obsolete for NMH to have a working farm, so its function now is purely educational. Students get to experience farmwork for the first time. They tap maple, harvest zucchini, and till the soil. The presence of livestock like draft horses or goats or dairy cows on campus was a wonderful thing, and it brought joy to many students. But it was neither easy nor sustainable to manage, and in the end it was too taxing on the school’s resources.

The decision that the administration has made is a good one. But that leads to the question: where do we go from here?

Back the farm, actually.

I contacted the new farm director, Nancy Hanson, to find out what changes the farm was undergoing. And when I returned to the red barn again, I was a bit surprised to find that the place where the goats once stayed had been replaced by a shiny new tractor. The sight of stirrups and saddles still hung on the wall made me terribly nostalgic. Yet it wasn’t all sad.

As Nancy led me around the sunny grounds, I saw the farm take on a new light. Peeking out through the gray cover of the greenhouse, a couple cucumber plants were growing. We passed by rows of tilled soil where plants of all kinds stuck their green stalks out to greet the sun. I saw watermelon radish, squash, and zucchini.

“These will all go to the dining hall,” Nancy told me. “We’re hoping to plant some grapes and blueberries soon.”

A generous donation from alum Theresa M. Jacobs ‘10 has allowed NMH to expand its farm program and invest in more equipment– the shiny new tractor included– all of which will be going towards more vegetable plots, more experiences, more opportunity. Nancy told me that they're committed to growing a greater variety of fruits and vegetables, (which means more delicious, fresh food in the dining hall!) and are even looking to plant an apple and peach orchard.

By diverting resources from livestock to agriculture, the farm has set itself up for a sustainable, generational project; in a couple of months, there will be apple groves and peach trees set to bear fruit long after my time at NMH. I will miss Shorty, Belle, and the adorable cluster of goats. But the most important lesson that I’ve learned from the farm is that when you give something up, you gain something, too.